Master Metalsmith Ruth Penington

11 Minute Read

At the age of three, Ruth Penington created an apron for her doll, undaunted by the complexities of a pocket, hem, belt, lace edging and insertion of a blue ribbon. Today, seventy-five years later, an artist, designer/craftsman and teacher, she is recognized as one of America's pioneers in the field of modern jewelry and metalwork.

Very early, she was inspired and influenced to choose a life committed to art and to people. While there seem to have been no role models, there were plenty of teachers along the way whose philosophies encouraged the development of fearless individualism and of originality in the arts. Penington's life and art are marked by constant search, careful preparation, disciplined commitment and high expectations of herself and others. Her battles have been positive and constructive, dealing with such philosophical beliefs as the need for support of the crafts and humanities in the American university system and the advocacy of "hand crafts" in a hierarchy that valued the "fine" arts above all others.

Although one things of Penington as a Puget Sounder, she was born in Colorado Springs in 1905 and was taken to Seattle soon after. Art and handwork where her heritage from her immediate family, who gave her plenty of encouragement in all her pursuits. Even before her schooling began, she molded and sun-dried toy dished from clay she dug herself, and early in primary school she wove a wool rug with a design. Penington's paternal grandfather was a woodworker and a carriagemaker, who later built automobiles and airplanes. Her father was skilled with tools. Her mother, a dressmaker who designed elegant clothes, came from a family of Pennsylvania farmers who had to know how to do everything. This crafts atmosphere, combined with a philosophy of self reliance, was the first of many confidence-building milieus that shaped Penington's life and work.

When Penington was 14 years old, Lulu Hotchkiss, a teacher at Seattle's Lincoln High School who had previously taught in Chicago and Hannibal, Missouri, came into her life. Hotchkiss transmitted to Penington the esthetic gospel of the philosopher-historian Ernest Fenollosa and the artist-teacher Arthur Wesley Dow. This team, working in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, interpreted to Americans non-Western art, including Oriental, primitive, and archaic art, in new esthetic terms with social overtones. European academic art, dominant since the Renaissance, emphasized copying nature through the use of geometric perspective and modeling in light and shade. Opposing such principles, Fenollosa and Dow taught that the artists should use the "synthetic," or "structural," method of selecting from limitless visual possibilities and arranging expressively those that would create the most original and pleasing work of art.

Fenollosa's theories were not confined to painting but encompassed all three-dimensional work and all materials. "At creative periods all forms of art will be found to interact, From the building of a great temple to the outline of a bowl . . . all effort is transfused with a single style" He held that "Art . . . requires . . . freedom and trained selectivity, for only in this way can an artist discover that unique arrangement which is beautiful. To live artistically, in this sense, is to live as an individual." Fenollosa seems to have expected that the artist trained in making esthetic choices would transfer this ability to making choices in everyday life. He "felt sure that if a citizen developed an artist's eye would never conform timidly to narrow rules of living and the deadening pressure of the average." He further believed that artistic creativity depends on a free society with a climate of intellectual freedom and that the best art has been produced in such periods.

While Fenollosa concentrated on theory, Dow, as head of the Fine Arts Department at Columbia University's Teachers College, was in a favorable position to spread their ideas throughout the schools of the United States. His best-known book, Composition, was the educator's bible. It taught a three-part system, which emphasized line, color and especially, Notan—a Japanese term meaning "dark and light" or well-spaced "massing of tones of different values," not to be confused with the European notion of "life and shade," or modeling. Fenollosa's theories and Dow's system, as demonstrated by Lulu Hotchkiss in her drawing classes, had a profound effect on Penington. Her options for a career in art were wide open in this liberated atmosphere, where no one suggested that any one medium was more important that another.

After graduating as valedictorian of her class, Penington entered the University of Washington and began a 46 year association with the School of Art, first as student, then as faculty member. From the beginning, she was surrounded by teachers trained in the Dow system at Columbia. Central to her continued indoctrination were Walter Isaacs, painter, and Helen Neilson Rhodes, printmaker and design teacher. Penington remembers Rhodes's woodblocks, with their contrasting values, and her teaching of design with emphasis on "dark against light, light against dark . . ." as the embodiment of the Notan theory. Others on the faculty, many of whom had studied in Europe, were also schooled in the Dow system. Penington's early training was reinforced later by a year of study at Columbia Teachers College in 1929 and a summer with a Dow disciple at the California College of Arts and Crafts in 1935.

Penington speaks of the range of resources open to students and faculty at the University of Washington. The School of Art had a close tie-in with the School of Home Economics' classes in the history of textiles and techniques and with the anthropological museum, the Henry Art Gallery and the School of Business. She says, "We were on good terms with the College of Architecture, the College of Engineering, the foundry, the machine shop and with the Seattle Art Museum in Volunteer Park. We also benefited from the many visiting faculty member, including [Amédée] Ozenfant with his understanding of modern art and [Alexander] Archipenko who brought the European tradition."

As early as the mid-twenties, when all students in the University of Washington's Department of Painting, Sculpture and Design took the same basic courses, Penington worked in many media division appealed to her. "Metal can be made richer on the surface and freer in form than just drawing" By the early thirties she had become proficient enough in metalwork to be invited to show at the Seattle Art Museum, and in the forties and early fifties she also exhibited woodblock prints on both textiles and paper. Her jewelry and holloware were first seen nationally in invitational exhibitions held at the Baltimore Museum of Art and the Cincinnati Art Museum in 1944.

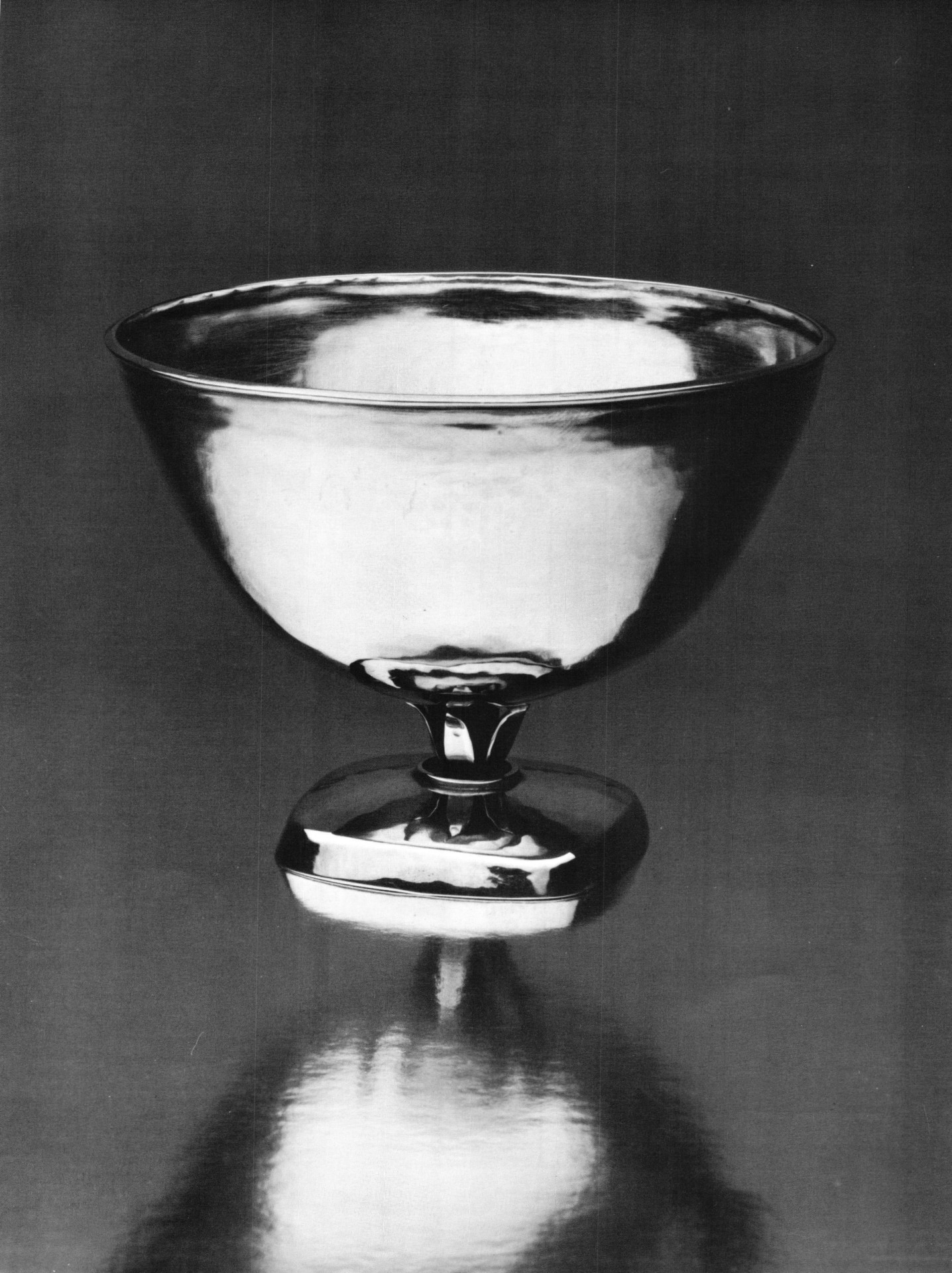

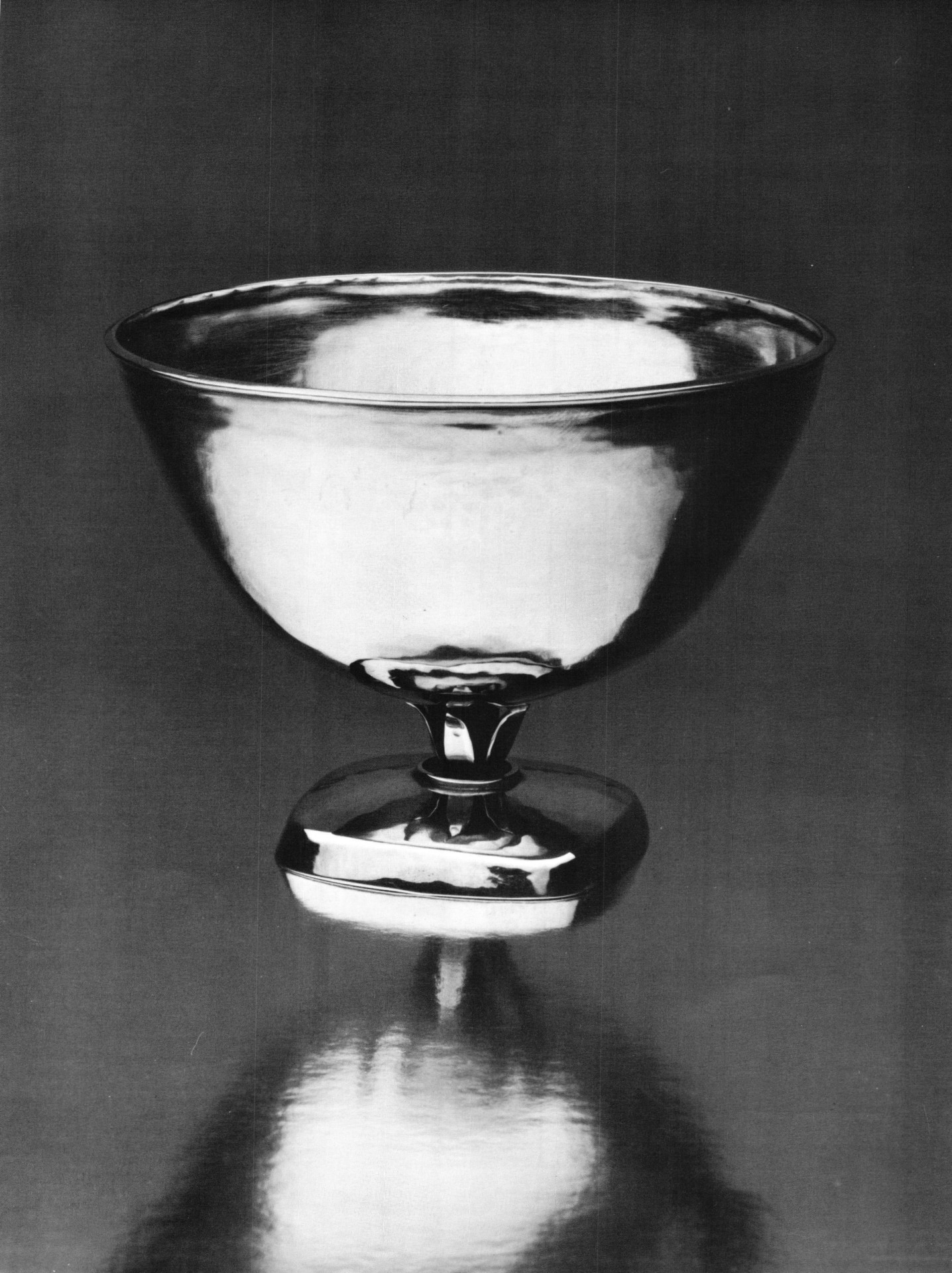

Penington's metalwork has moved in two parallel directions: richly encrusted works of visual delicacy and those marked with a monumental feeling, as if she were thinking architecturally and expansively in the planning stages. In these last, provocative in their time, large, flat and simple areas are related to other large, simple areas contained within a generous form. Her mentor, Walter Isaacs, emphasized this "bigness," saying that searching out "the larger elements of truth in painting the figure" paralleled the approach of the design student, who "is usually trying to create forms. But in each case the work must proceed from large forms into smaller parts."

Penington was a leader in developing jewelry that is monumental in scale, so much so that juries sometimes rejected her work because it was "too big to be wearable." Although many of her pieces are large, they are comfortable to wear. She says, "The material, the techniques, the scale of the wearer, the functional aspects all dictate the approach." On the occasion of Penington's retrospective exhibition in 1962 at Seattle's Henry Art Gallery, Isaacs wrote to her, "It is as if metal were clay in your hands. You have risen above the difficulties of the craft and heave reached expression."

Penington's work draws generously on archaic and primitive arts for inspiration and she makes use of spindle whorls, trade and tomb beads, amulets and feathers. She also incorporates forms and decorations inspired by Byzantine, Viking, pre-Columbian, North American Indian and other art, sometimes combining several traditions in one piece. "Today we have easy access to all of history and all of the world. Technicians are skillful and may continue to use the old patterns. But why copy work when someone did better?"

Moved by the urgings of such activists as Lulu Hotchkiss, Walter Isaacs and Helen Rhodes, and by the encouragement of her mother and the educational theories of John Dewey, Ruth Penington enlarged her world. In 1934 she began to travel in the United States and abroad, following Isaacs' advice to learn from art, not just from slides and books. Among the areas she visited were Europe, Russia, South America and Japan.

After Penington's advanced training at Columbia's Teacher's College in 1929, she attended the Carnegie Art Program at the University of Oregon in 1931 and 1932. She worked with Gilbert Rohde in New York City for a year in 1944; with English silversmith William Bennett at a Rhode Island School of Design workshop arranged by Margaret Craver in 1947; and in the shop of A. Michaelson in Copenhagen in 1952. She taught at the University of California, Berkeley, in the forties and at the University of Alaska in the fifties. In 1955 she established her own Fidalgo Sumer School of the Allied Arts in La Conner, Washington.

Ruth Penington was a founding member of organizations established to help artists and craftsmen. They include Lambda Rho, an honorary art society at the University of Washington; the Northwest Printmakers' Society; Northwest Designer-Craftsmen; and Friends of the Crafts in Seattle; as well as the World Craft Council in New York City. In 1950, she was the leader in establishing the long-lived Northwest Crafts Exhibition held at the University of Washington.

n 1954, as a member of Aileen Vanderbilt Webb's American Craftsmen's Education Council, Penington was involved in a conference at The Art Institute of Chicago called together for the purpose of encouraging the regular exhibition of handcrafts in the nation's art museums. In 1962, she was largely responsible for the inclusion of an exhibition of work by Northwest craftsmen in Seattle's Century-21 Exposition. In recognition of her long years of service to the American Craft Council, Penington was named Trustee Emeritus and Fellow in the seventies.

Much about Penington marks her as "Northwestern." She loves the land and has never thought of leaving it. She has been moved by Northwest Coast Indian art and Oriental art, both part of the Northwest heritage. She has used Northwest found objects such as unpolished beach pebbles and agates in her art. She has fought long and hard for the good of Northwest institutions and artists. But her philosophy and her art are far from regional. She has been inspired by many cultures, archaic and contemporary, and her approach to art is universal.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

"I had my very first work in silkscreen printing with Ruth. I learned the rudiments in this only formal education I ever had in silkscreen, which has become so important to my career. Her personality too—easy, sisterly rather than stern—helped me to grow in confidence and to take things less tensely and perhaps, as important, I learned so much from her about lifestyle and the enjoyment of life. I was going through a temporary idealism in which I wanted no possessions. Ruth began to wear new dresses, simple white jewelry—all this setting off a new suntan—such freshness. I realized that this was not vanity, but her gift to us—to come on wonderfully and I began to think of possessions as a way of sharing, and family and friends were all the more grateful for it."

- JACK LENOR LARSEN, designer

"She was tough and professional and demanded excellence—too bad there aren't more like her in academe."

- PHILIP MCCRACKEN, sculptor

"She sang a bit in class. I think she has some vaudeville in her veins. Once I melted down one of my projects. She said 'don't worry' and then flunked me! I loved her strong personality."

- IRWIN CAPLAN, humorist and cartoonist

"She was a leader in developing the excitement of the craft movement. She had a profound effect in building patronage for the crafts."

- RUSSELL DAY, jeweler and teacher

Notes

All passages in quotation marks are from the interview with Ruth Penington unless otherwise indicated.

- Seattle Public School Archives.

- Lawrence W. Chisolm, Fenollosa: The Far East and American Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963), p. 194.

- Ibid, p. 205.

- Ibid, p. 9.

- Ibid, p. 4.

- Ibid, p. 206.

- Arthur Wesley Dow, Compositions 1899 (New York: Doubleday, Doran, 1929).

- Ibid, p. 59. Re: Notan "Dark-and-light has not been considered in school curricula, except in its limited application to representation. The study of 'light and shade' has for its aim, not the creation of a beautiful idea in terms of contrasting masses of light and dark but merely the accurate rendering of certain facts of nature—hence is a scientific rather than an artistic exercise."

- Walter F. Isaacs, "Dow and the Modern Painters" (M.S., University of Washington, School of Art Library, n.d.), p. 4.

- Isaacs to Penington, author's possession.

Reprinted from Archives of American Art Journal, vol. 23, no. 2, 1983 with permission.

LaMar Harrington, formerly director of the Henry Gallery of the University of Washington, interviewed Ruth Penington in Feb., 1983 for the Archives' Northwest Oral History Project.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Svenja John: Technoid Handicrafts

Measure and Alchemy

Gemstone Cutting Creates Freedom for Design

The Best Jewelry Books: A Comprehensive Reading List For Craftspeople

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.