The Jewish Ceremonial Objects

21 Minute Read

Jewish ceremonial objects have been in production since ancient times. Periodic migrations, voluntary and otherwise, distributed the Jewish people throughout most of the world. The surrounding non-Jewish cultures sometimes played either a benign or harmful role in influencing the nature of Jewish rituals and the design of ritual objects.

If you look at Jewish ceremonial pieces in museums, books and auction catalogs, you become aware of certain common features: the extant objects were made between the 17th and late 19th centuries, mostly of silver, in the baroque, rococo or neoclassical style. Earlier pieces rarely survived. As in secular metalwork of the time, the chief decorative techniques were repoussé and engraving. Casting was also common, especially in brass pieces. Most of the objects are European in origin, though there are examples from North Africa, the Middle East, India and China. Western European work was made by Christian silversmiths since guilds generally excluded Jews.

The late 19th- and most of the 20th-century works are not well represented because the industrial age led to a decline in the number of silversmiths and esthetic decay in the decorative arts. Factory-made ritual objects were corruptions, third-generation rehashes of the older, more authentic styles and for good reason are not often seen in museums, books or auction catalogs.

In 1906, with the founding of the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts in Jerusalem, Palestine became an important center for the craft production of ceremonial art. Early Bezalel designs appear to derive from the Middle Eastern style, European decorative arts and hints of Art Nouveau, Art Deco and a noticeable helping of what looks like the public school manual-raining class style of the 1930s and 1940s in America. This is not surprising since Palestine was, as Israel is now, a mosaic of many cultural influences. With the high-speed absorption of refugees from pre-war Germany and post-war Europe in the 30s and 40s, the esthetic balance shifted to a modernist style, which Israeli metalsmiths continue to favor.

In the United States, handcrafted ceremonial art is rare between the 18th-century silver of Myer Myers (the first Jewish silversmith in the colonies) and the work of the idiosyncratic Ilya Schor, who emigrated from Poland in the 1940s.

The esthetics of Jewish ceremonial art was revolutionized in 1931, at the Berlin Museum of Arts and Crafts, where a young sculptor/metalsmith, Ludwig Wolpert exhibited a silver and ebony Seder (Passover) dish. It was a pure expression of the spare, geometric, functionalist style that we now associate with the Bauhaus in particular and modernism in general. With this piece, Wolpert initiated a radically new style in the design of the ceremonial object. He believed the design of those objects should not be rooted in the past but should reflect the esthetic personality of the period as interpreted by the artist. Wolpert became the first widely known artist to make ceremonial Judaica a life work rather than the focus of an occasional commission. In 1933, Wolpert fled Nazi Germany and arrived in Palestine, where he joined the faculty of the Bezalel school. His reputation eventually grew to international scope.

In the years following World War II, a boom in synagogue construction in the United States led to an increased demand for ceremonial art. Dr. Abram Kanof, who in the early 50s was chairman of the board of the Jewish Museum in New York, saw the opportunity to rejuvenate the design of ceremonial objects. He anticipated that contemporary religious architecture would require a suitable style of synagogue art.

He also believed that the availability of modern domestic ceremonial objects might encourage young people to maintain their religious identity and continue to observe the traditional ceremonies at home.

In 1956, with the financial support of Dr. Kanof and his wife, Dr. Frances Pascher, the Jewish Museum opened the Tobe Pascher Workshop. To guarantee that the "modernist" style would prevail, the Museum invited Ludwig Wolpert to reach and be the workshop director. Since the execution of one-of-a-kind pieces by hand was slow and expensive, prototypes for mass production were preferred, and Wolpert did these, as well as numerous commissions.

When Wolpert died in 1981, Moshe Zabari, who had been his student in Israel, was appointed workshop director. Wolpert's daughter, Chava W. Richard, a designer and enamelist, and Harold Rabinowitz, a former workshop student, are currently in residence. Richard designs prototypes for production and Rabinowitz concentrates on individual pieces. The workshop now offers two $500 fellowships a year for selected candidates who are already technically proficient and want to learn the specifics of ceremonial art. In my opinion, the contemporary style in Jewish ceremonial art in America began with the arrival of Ludwig Wolpert and Chava Richard and was reinforced in 1961 when Moshe Zabari came to assist Wolpert. They were unique in another respect; no other craftsmen at the time were limiting their practice to the design and execution of Judaica. The Tobe Pascher Workshop was the first in this country and remains the only one in the world exclusively devoted to ceremonial art.

I have devoted a lot of space to the workshop, but some mention should be made of other craftsmen working during the early years of the movement. Ilya Schor was active during the 40s and 50s. He was the only important ceremonial artist at the time, until the arrival of Wolpert. His style was distinctive and at odds with the Modernist Movement. His surfaces were executed using a combination of shallow repoussé, piercing and engraiving. They were ornamented with Hebrew lettering and caricaturelike human figures, animals, birds, fish and foliage. His imagery is reminiscent of the work of Marc Chagall and relies on Eastern European Jewish folklore and Biblical material.

Kurt Matzdorf has been deeply involved with ceremonial work since the 50s. Considering the comparative youth of the American ceremonial art movement, Matzdorf ranks as one of the pioneers, as does the late Maxwell Chayat, who used a flame-shaped motif enough to make it a signature of his work.

This brief overview of Jewish ceremonial art production in America is intended only to establish a context for the following discussion of the "Ten by Ten" show. A history of the field from colonial times to the present has not been written. If such a study is undertaken, I would anticipate that a surprising amount of unknown work would come to light.

The Jewish Ceremonial Objects Today

The National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia is a small museum with a big heart. Unlike the larger Jewish museums in New York, it chooses to pay enthusiastic attention to the recent and historically unprecedented flowering of interest among craftsmen in the making of Judaica.

Recently when I was there, four different exhibitions were in progress: a historical exhibit consisting mostly of photographs, the permanent exhibit of ceremonial art, the gift shop display and the "Ten by Ten" show. The theme of the show was to invite 10 stellar artists to submit one of their best pieces that exemplify today's finest Jewish ceremonial art. It involved imagination and confidence to mount this show, since Jewish ceremonial art is historically conservative.

Most of the rituals are hundreds, sometimes thousands of years old. The clientele has a justifiable fear of the rituals losing some of their sanctity if the objects appear to stray too much from familiar forms. Economic concerns have an impact. Handmade work is expensive and silver, the traditional material, adds to the cost. There is a predictable tendency on the part of the purchaser to protect his investment by avoiding work that seems extreme. Sometimes there are restrictions on a design based on Jewish lore or law. Tradition calls for a marriage of the beautiful, the legal and the practical, and, if the restrictions are not honored, the object becomes ritually unacceptable.

In the case of the "Ten by Ten" exhibit, the museum got what it wanted—a breath of fresh air, a departure from conservative canon. What follows is my reaction and interpretation of the pieces on exhibit.

Kurt Matzdorf

Kurt Matzdorf's silver and acrylic Torah finials and shield use historical iconography in a decorative though modern style. For instance, there are two basic motifs dominant in the traditional design of Torah finials. One is architectural, essentially a tall belltower, or campanile, form. The other is the bulbous form inspired by the pomegranate, an important Middle Eastern and Biblical symbol. Matzdorf has selected the familiar pomegranate form with crown on top and bells below. The use of 12 tribal symbols, each contained within a tent-shaped frame, also indicates that he has taken the time to do the necessary research into Jewish symbolism.

I found myself questioning the use of the glossy, colored plexiglass in combination with what is essentially a historically based design in silver. The use of vitreous enamels may have reinforced the image of sumptuousness and skillful execution projected by the pieces, while the plastic creates ambiguity because it is an industrial material known for its pejorative connotation. Possibly Matzdorf wanted to impart a contemporary look to the design, but for me the effect is one of conflict.

Frann Addison

Frann Addison pioneered the use of beveled glass and pewter. Its nostalgic overtones appeal to the reverence for tradition, an important component of ceremonial art, yet the effect remains up-to-date. Addison has succeeded in achieving the best of both worlds. Her Sabbath candelabrum takes its formal cue from the architectural motif of a traditional bench-style Hanukah lamp. The glass shapes reinforce the architectural theme and reflect the candlelight to create an aura of intimacy.

Technically, the use of pewter sheets that are too thin weaken the piece visually and structurally. The design is based on flat surfaces, yet they are rippled, and the thin knife-like edges are not in proportion to the size of the object. Esthetic and technical indecision is projected when corners that should be 90 degrees, edges that should be straight and surfaces that should be flat are slightly off the mark. It gives the impression that the attempt was made but just missed. On the other hand, a deviation from a form that clearly does not attempt perfection is never noticed.

To Addison's credit, her piece was the only metal object in the show using Hebrew lettering. Traditional pieces almost always had inscriptions whose lettering was handled in a straightforward, unimaginative manner. But silversmiths' goals were different then. Ludwig Wolpert made the Hebrew alphabet an art form, using it as symbol, ornament, communication and structure. If Frann Addison is going to continue to use the alphabet. I think it would be profitable to avoid depending on a standard, one-style-fits-all letter form and to let the style of the object suggest the style of the calligraphy, just as the function of the object suggests the content of the inscription in the first place.

Janet Dash

Janet Dash's articulated Hanukah lamp, consisting of four horizontally linked triangles, is a clever and attractive addition to the family of ceremonial objects including those that fold up for traveling and the do-it-yourself design, which one can alter by rearranging the parts. To chop up thin metal sheet on a squaring shear like paper and to cut off lengths of off-the-shelf metal tubing like sausage, and to solder it together, is to abdicate responsibility for the design.

Metalsmithing is time-consuming and expensive, but the design will go on living for centuries after the time and money spent have been forgotten. To hold back is to guarantee that the piece won't make it. The esthetic promise of this unusual object was betrayed by its thinness, the use of as-is stock shapes and the mechanical weakness of its linkage system. It sits on the edge of being a three-dimensional maquette in paper that happens to be executed in silver. Now, that's expensive!

David Aronson

David Aronson's limited-edition sculpture is a large (17¼") gold-plated cast bronze Hanukah lamp. It bears a title Angels of Light and makes use of the archetypal Menorah form. Aronson's lamp has four semicircular concentric branches radiating from a thick, rather clumsy-looking central column. That column, resembling a tree trunk, may have taken its form from the "tree of life" theme, to which the Menorah of the Bible, with its seven foliate branches, is related.

The symbolism is apt but the column still lacks grace. Distributed in front of the arms of the candelabrum, obscuring much of it, and apparently dangling in space, is a group of modern "angels" with skirts flapping, like middle-aged matrons doing a frantic imitation of Mary Poppins. The branches have sockets for candies, so the piece is functional, yet there is a "neither-fish-nor-fowl" quality about it. It wants to be a functional ritual object but it doesn't want to relinquish the undeniable status that goes with the territory owned by sculpture. The use of figurative imagery, either flat, in relief or in the round is very common in traditional Jewish ceremonial objects, in spite of the Second Commandment's proscription against the making of graven images.

This is not the problem. Aronson has focused on the human figure in his work as a sculptor and handled it with sensitivity, humor and imagination, as well as skill. The problem is that there is a difference between a sculptural Hanukah lamp and a sculpture-as- Hanukah-lamp, wherein the lamp aspect, with its candle sockets, is treated as a kind of afterthought, secondary to the sculpture. Aronson's use of a stereotyped Menorah motif as background for the sculptured angels supports this interpretation.

Leon Lugassy

Leon Lugassy's Lulav holder is a place to rest the Lulav, a palm branch about three feet long, bound together with willow and myrtle sprays. The Lulav is an indispensible pan of the ancient Succoth festival, but when it is not being, carried it has no resting place. Lugassy's solution, a wooden organic form with Art Nouveau styling, complements the agricultural spirit of the festival.

Sharon Norry

Sharon Norry submitted a Torah case, which is a container for the Torah scroll used by some Sephardic (Spanish) congregations. Traditional Middle Eastern versions were usually made of heavily repousséd silver laid over a wooden carcass. A pair of Torah finials usually projected from its top. Norry simplified the design by using a plain cylindrical form and substituted textile for silver. The minimal character of the form is balanced by a colorful and energetic needlepoint representation of the familiar symbol of hands giving the priestly blessing. This is rendered in a geometric, abstract style, which is a refreshing departure from the trite anatomically literal version usually seen in commercial work. It is a good example of the use of well-known iconography in new, subtle, visually exciting ways.

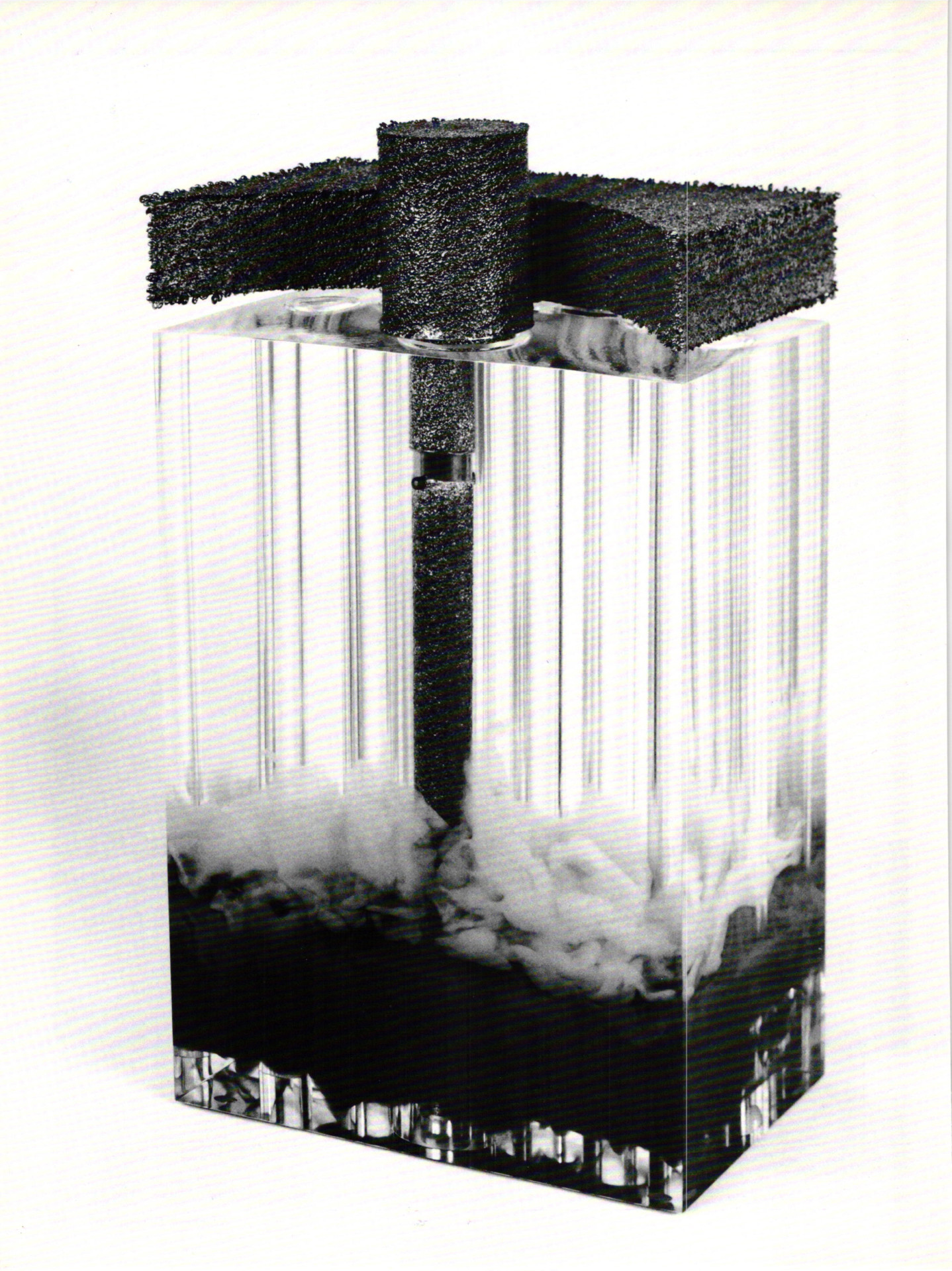

Stanley Lechtzin

Stanley Lechtzin's cast acrylic Mezuzah typifies some important aspects of his style: the intense exploration and adaptation of modern industrial processes and materials, the impulse to innovate, technically and esthetically, to constantly stretch the boundaries imposed by convention, to execute work with skill that exceeds human expectations. So, it is not a surprise that the Mezuzah is a bravura statement. The piece is essentially a violet rectangular block of acrylic 15½"h by 10⅜"w by 4⅜"d. It rests on a low, slightly smaller base, has a flat top and vertically oriented flutes that have been milled into the corners and the back surface. The fluting is intended to suggest a column, which, in turn, relates to a door post. The word Mezuzah means "doorpost." There are embedments in the cast acrylic: the Hebrew passage from the Bible in white calligraphy, two stalks of wheat bordering the inscription and what appears to be light-colored plastic foam filling the bottom third of the block.

Because of its monumental size, the Lechtzin Mezuzah departs radically from the doorpost context of the traditional object and thus also excludes itself from conventional forms of evaluation and criticism applied to these artifacts. If I look at it as a Mezuzah, it evokes mostly negative reactions, because it is pretentiously oversized compared with traditional Mezuzahs. lf I look at it as sculpture, my attitude is more positive. The basis for ritual objects as found in the Talmud is the enhancement of religious rituals. There is no implication that the ceremonial object should divert attention from the religious experience itself. On the contrary, there are customs and practices designed to discourage a shift of concentration away from the observation.

This Mezuzah because of its size, color, the calligraphy floating in space, its ethereal glowing presence, its almost jukebox optical qualities and shape, maybe even its subtle suggestion of a sacrificial altar from another planet, announces the presence of the artist and takes on a life and importance of its own. It almost wants to be worshipped itself, like a graven image.

Traditional Judaism does not encourage asceticism and irrational self-denial, but it also frowns on excess. The fact that excess and misdirection of priorities exist in life is easy enough to see in the way some Bar Mitzvahs are celebrated. Unfortunately, the significance of the Bar Mitzvah, the leading of a consecrated life, seemed to shrink at the same rate as the big parry grew. The sense of proportion has somehow been compromised. In Lechtzin's Mezuzah, the small size of the inscription in relation to the large size of the block indicates a similar disproportion.

A Mezuzah is a small container, usually not more than a few inches long, that is often made of inexpensive materials such as wood, brass or tin plate. An extravagant one might be made of silver, but its size prevents it from taking on airs. It contains a small parchment scroll and is attached to the right hand doorpost of a Jewish home. The inscription on the scroll is the affirmation of faith, and the object of the Mezuzah itself is to serve as a reminder of that. Its function as a reminder is more easily carried out if it is placed where it will be seen often, so one of the places where the Bible said these beliefs were to be affixed was the doorpost.

Strictly speaking, the Lechtzin Mezuzah being too massive to fit on a doorpost, is not a Mezuzah. The absence of a handlelettered parchment scroll also renders it nonkosher, not fit for ritual use. If the intent and not the letter of the Biblical law is considered, then this impressive object is an important contribution to the ongoing process of thinking about traditional forms in untraditional ways. If I picture it installed in the average home, I get vibrations similar to those evoked by the image of the opulent Bar Mitzvah, the ratio of pomp to piety seems unbalanced. The scale of the piece demands an appropriate setting, and my personal vision of a house of worship as a place for religious art as well as prayer would be satisfied if this Mezuzah-as-sculpture would be placed, along with other Judaic art in a synagogue or temple.

Daniella Kerner

Daniella Kerner's Havdalah set The Separation presents a similar set of philosophical problems. Havdalah means "separation" in Hebrew. It refers to the separation between the Sabbath, a holy day of rest, and the other days of the week. The sacredness of the Sabbath is emphasized by Putting a frame around it, so that the symmetry of the frame consists of a ritual that marks the beginning of the Sabbath on Friday at sundown, and the Havdalah ceremony, that marks its end on Saturday evening. The ritual involves the sipping of wine, lighting of a braided candle and inhaling the aroma of spices. Special blessings are recited before each of these acts. The traditional ritual accessories to the service are a wine cup, a candle holder and a spice container. These are often kept in a tray, which only serves as an organizing utensil. The mood of the ritual is warm, friendly, neither riotously joyful, like the Purim hilarity, or melancholy, like that on Yom Kippur. There may be a touch of sadness at the departure of the "Sabbath Bride," but that is as far as it goes.

Kerner's Havdalah set is physically similar to the Lechtzin Mezuzah. It is a large, rectangular block of clear cast acrylic. It also has embedments and includes four electroformed metal objects that lit in or on the block. It is not easy to determine which one serves which purpose without studying the piece. There is no indication that it is a Jewish ritual object. As to the absence of any identifying lettering or symbols, there are no laws that require this in a Havdalah set, nor do the pieces need to telegraph their function. But logic demands an answer to this question: Why bother going to the trouble and expense of making a ceremonial object, especially a very large one, if an ordinary salt shaker can serve as a spice container and sacramental wine can be sipped from a drinking glass? A decision to avoid the use of indentifying iconography is a personal matter. An artist may argue that he compensates for this by designing the forms to make the ritual use clear. But in this Havdalah set, the three functioning parts are stacked to form a single column. Therefore, instead of suggesting their function, they obscure it further. The result is that the object had the opportunities to identify itself and it didn't. This invites the viewer to interpret its message in a projective way, based on what is visible, like an ink blot test.

The metal parts are electroformed copper with a very nodular coarse texture that does nor invite touching. You would not want to put the wine cup to your lips. The forms are minimal, geometric, cold and forbidding. The color of the metal is rusty, and since three of the forms resemble tin cans, the combination of form, texture and color speaks of decay and disintegration. The contrast with the pristine, precise purity of the clear plastic augments the quality of each. The three stacked cylinders fit into a hole in the acrylic block. The first image that came to mind was of the radioactive fuel rods suspended in the water of a nuclear reactor. The embedded material at the bottom of the block has two layers. The top appears to be the same light-colored foamy substance Lechtzin used in his Mezuzah. The lower layer is darker and as it approaches the bottom of the block, it turns to a funereal black. My immediate reaction to the light foam was that it suggested illness: it resembled used surgical cotton piled in the bottom of a waste can. The black material, which is very granular, echoing the texture of the electroforms, looked like ashes.

The message of this piece, delivered by its formal attributes, spoke to me of a catastrophic event rather than a warm, family-centered ceremony. In this respect I applaud Kerner's talent for creating powerful, emotionally moving images.

I also saw the object as another, currently popular craft exercise, the metaphor for a functional object that doesn't function. Because , of their content, ceremonial objects are already metaphors and they raise the question. Why give up usefulness in order to achieve iconographic liberation, when the treasure house of images and the freedom already exist?

The Lechtzin Mezuzah, which is made of essentially the same material and has essentially the same size and shape does qualify as a ceremonial object because it has a Jewish reference and in order to function, it merely has to be visible. Its abnormal size, which may unsettle traditionalists, actually enhances its function, while the same exaggeration in size of the Havdalah set interferes with its function because it has to be used as well as seen. The somber mood it projects may not be in keeping with the tone of the ritual but at least the physical aspects of the piece should permit it to be used comfortably.

The National Museum of American Jewish History rates bouquets for this show on several counts: for selecting a group of artists whose work covered a wide-enough spectrum of orientations to make the exhibit stimulating; for taking the risk in showing work that was sure to jolt the responses of visitors who may have come with expectations rooted in past experiences of ceremonial art; and for being willing to remain almost alone among museums in committing itself to showing, on a continuing basis, what the new breed of ceremonial artists is accomplishing.

Readings

- Abram Kanof, Jewish Ceremonial Art and Religious Observance, New York: Abrams

- Mae Shafter, Rockland, The Jewish Yellow, Pages New York, Schocken Books, 1976

- Mae Shafter, Rockland, The New Jewish Yellow Pages, Englewood, NJ: SBS Publishing, 1980

- Jay Weinstein, A Collector's Guide to Judaica, New York: Thames and Hudson, 1985

- "Ten by Ten," Sixth Annual Invitational Craft Exhibition, National Museum of American Jewish History, 55 North 5th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106, November 16-December 31, 1986. An illustrated catalog is available free from the museum

Bernard Bernstein is a retired professor of metalworking and design at City College in New York, who studied the history of Torah ornaments for both his M.F.A. and Doctorate. He now designs and executes Jewish ceremonial work exclusively.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.