Conversation with Stanley Lechtzin on Olaf Skoogfors

9 Minute Read

This is an excerpt from an interview with Stanley Lechtzin about the life of Olaf Skoogfors. Olaf Skoogfors and Stanley Lechtzin were good friends during Olaf's teaching years.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Q. Can you elaborate on Olaf's experience at RIT and particularly his relationship with Ron Pearson?

SL: He and Jack Prip, who was also there at the time, developed a very, very close relationship with Ron Pearson, even though they were both rather senior to him. In reality when Olaf completed his studies and left RIT, he had become close personal friends with both Pearson and Prip.

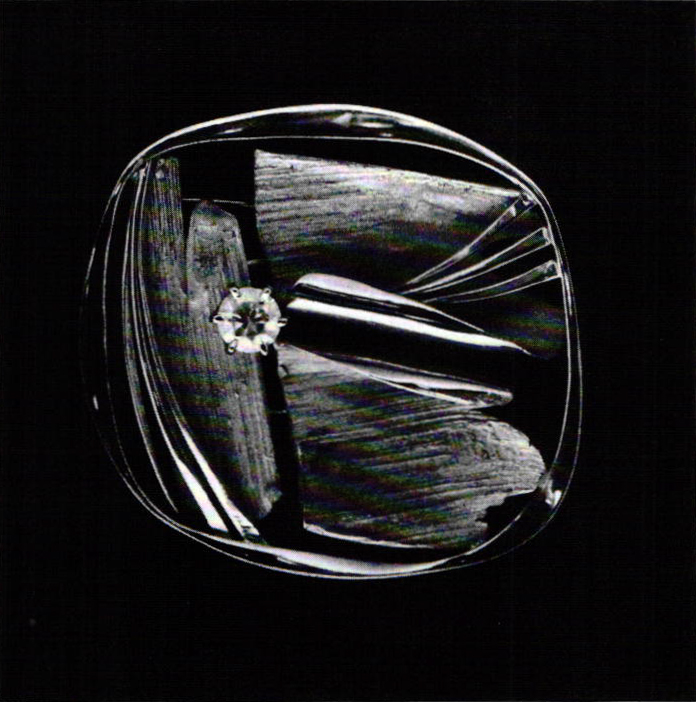

"I think of my pieces as compositions, in some cases, in alliance with the human body, but often as independent objects. This is particularly true in my pins which by their very nature allow this freedom."

- Olaf Skoogfors

Q. Can you pinpoint what OIaf would have taken away with him from these relationships?

SL: Pretty much what he said at the "Economic Alternatives" symposium: a knowledge of business practices and how one might go about producing work that would sell. And, eventually, that was Olaf's expectation, that he would come back to Philadelphia, set up a shop, which he did—and I met him at the transition point from running his own shop and selling his own production work to becoming a teacher at PCA. The latter occurred in the summer of 1962. We both began teaching in the fall at our respective institutions. But Olaf never really expected to be a teacher.

Q. Can you speculate on the relationship between craft, design and painting (abstract expressionism) in the 50s and 60s and how that might have had an influence on Olaf's work?

SL: Much of what we were doing partook of some of those same attitudes. I think the attitude of direct work in the medium was one that pervaded the art community. It wasn't abstract expressionist painting per se that affected our work as much as just that attitude, which you found in all the schools and all the studios, the feeling that you need not make careful models and careful drawings and precise plans, but you can just walk into the studio and begin making art. And that is a break from the industrial design attitude that permeated the 50s and early 60s, and when I talk about industrial design, I lump Scandinavian design into it, because the Scandinavian stuff that so influenced us at that time was designed by and large by architects. And it was designed for factory production. So, picking up a piece of metal and putting a torch to it, or picking up a piece of metal, cutting it and adding it to another piece of metal was something that wouldn't have been possible without the attitude I was just discussing, which was typified by the abstract expressionist painter, by the Jackson Pollocks, etc. I don't know that all of us were directly influenced by the painting attitudes, but the attitudes in society and in the art world do affect us. Olaf was much more aware of and much more responsive to the painting community than I would have been, or than I think Pearson or Prip would have been at that time.

Q. How was that manifest: did he actually have friends who were pointers or did he go to museums a lot?

SL: He maintained professional relationships with painters in the Philadelphia community. And we discussed at length the reasonableness of relying on or going to other media, other disciplines, as sources. I have always taken the position that it isn't reasonable to do so, whereas he would take the position that it seemed perfectly appropriate. And much of that was conditioned by his father-in-law, Louis Gessensway, who was a composer and a performer with the Philadelphia orchestra. Olaf was very interested in developing correlations between his work and the work of his composer/father-in-law. They shared a home, so there was that interaction. Louis Gessensway very often would describe Olaf's work in musical terms.

"In more recent times I have been interested in the strength/vitality of barbaric, primitive and peasant deaign, and in my own way I'm trying tocapture that vitality in my work. I believe jewelry must be wearable, but have a strong, forceful image as well. It should not just be casual decoration, but a reflection of the creator and the wearer."

- Olaf Skoogfors

Q. The other side of one's personality has to do with how you look at society and how you look at politics. Was there any correlation between a political stand or social critique and OIaf's jewelry at the time?

SL: No, I don't think his jewelry at any time became a vehicle for social comment. However, his knowledge of economics and his attitudes about economics governed his business life.

Q. But was politics a constant source of discussion as much as painting or jewelry?

SL: Olaf's life was one that was very committed to his political involvement with socialism. This was an ongoing commitment of his, and I would say a week wouldn't go by in which he wouldn't have had some active party activity to engage in. But I don't think it affected his art in any way that I could describe. I think Olaf agreed with me that he would find no way to use his work for social comment. There are much better media for effecting social change than jewelry. Olaf was involved in esthetics when he sat down at the bench.

Pendants | |

Q. What if anything did OIaf invent in terms of design, and what survives as an influence?

SL: In terms of esthetics, it's hard to put into words what is clearly Olaf Skoogfors. When I see it, l know it, when I see it turning up in other people's work, I know it immediately. But I can't define it. And I would say that that is perhaps its strength. It is purely a visual experience. But his legacy is there. It turns up often enough for me to know that somewhere or other people have been exposed to Skoogfors. There's a poetry there, that's the only way I can describe it. In many ways I respond to Olaf's work as I do to Miyé Matsukata's work. It was very personal, very sensitive. I feel that his major contribution was the enhancement of jewelry as an art form in this century. I think he's one of the real artists in the field.

"Two aspects of jewelry interest me the most: The image itself and the characteristics of the material from which it is made."

- Olaf Skoogfors

Q. What was his contribution as a teacher?

SL: He excited his students. He changed the lives of virtually everyone who studied with him. I don't think it was in the form of establishing unique curricula or providing unique technical information. I think he was a role model. I think that kind of wit and sensitivity and concern is the contribution he made in the classroom.

Related Articles:

Stanley Lechtzin is chairman of the Craft Department at Tyler School of Art

Quotes throughout by Olaf Skoogfors, 1969-1975. Captions and commentary by Judy Skoogfors

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.